Oxford Cancer Analytics raises $11M to detect lung cancer via a blood test

OXcan combines proteomics and artificial intelligence for early detection

Read more...In 1994, Jerry Yang and David Filo started a project in a trailer on the grounds of Stanford. The two were electrical engineering graduate students at Stanford and named their project, “Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web”. In January 1995, the two officially changed the website’s name to Yahoo!. But even before the name change, the website already passed the million-hit milestone. Nevertheless, Yahoo!’s seed-funding was truly FFF – friends, family, and fools – in the early days. Which is why, when Michael Moritz of Sequoia Capital did two rounds of Series A funding in 1995, he was able to invest only $3M and walk away with about 30% of one of the most profitable .com businesses. Life was simple then. VC’s had a clear understanding of what they had to do: raise a fund in the $10-$20M range and spread the wealth around to a portfolio of a dozen companies. The portfolios would be carefully labored over and only big ideas worthy of big risk would be accepted.

But that was 1995. When the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (TRA97) was passed and lowered the maximum tax rate on capital gains for individual investors, the market responded with wild volatility towards non- and lower dividend-paying stocks. The additional incentive to invest in these stocks drove the prices of many .com companies through the roof, highly inflating their worth. IPO proceeds from 97-2000 saw unprecedented numbers – hundreds of millions of dollars. In 2000, when the bubble burst, the NASDAQ tumbled over 4,000 points. No one was spared the burst; Yahoo! shares fell from $118 in 2000 to just over $8 in 2001.

And since that bubble burst, the economy still hasn’t recovered. A lot has been done to turn the tides on a lot of this, but even today the market is still thousands of points lower than the levels it reached in the mid-90s. With all the terrible collapses and the billions lost on sock-puppets and companies that began with “e-”, VC’s became frightened of the tech market. In the early and mid 90s, an entrepreneur could put together a $1-$5M Series A on nothing more than a great idea. Following the bubble, that same entrepreneur would be lucky to get her foot in a VC’s door. Venture Capitalists were hurt and scared following their mistakes in the bubble and they scaled back their operations. The economy remained strained for much of the mid-2000s and, following the great recession in 2008, VC’s retreated even further.

We are now 13 years after the .com bubble and I can tell you that Venture Capitalists are still wary. The traditional VC-backed Series A comes much later for a company now. They might be loosening the purse strings a bit, but if you want any hint of VC money now a days, you have to provide so much more than in the early 90’s. But this is a good thing.

The early and mid-90s were characterized by a lot of really poor investing on weakly thought out principles that lead to the near complete collapse of a burgeoning industry. Growth over profits will never work for sock-puppets. It is good that we know that now and that VC’s are requiring so much more. Great ideas are still necessary, but now a solid Series A requires tangible proof in every single metric you can imagine, and they all have to point to you scaling in the right direction.

Closing your Series A will net you $5-$30M now, but only if your business looks good enough to merit that money.

Under the current state of affairs, the majority of startups that are seeking Series A don’t make the cut.

Here are two reasons why that happens:

As firms raise larger funds, they run into a problem – it’s hard to just invest in more companies. The size of their fund is now larger than they were historically, but this comes with consequences. Their monetary capital constraints are lifted, but they still face human capital constraints in the form of board seats and other administrative duties. So rather than increase the number of companies they invest in, VC’s are all but forced to invest more into each of their painstakingly selected portfolios companies.

With increased scrutiny of each deal, it follows that they’ll choose to invest in only the best companies and say ‘next’ to the rest. As I hinted in point 1, they can’t invest in 50 companies because that spreads them thin and leads to bad outcomes, which in turn will hurt their ability to raise their next fund in 3-5 years.

Re-read the two points above. This is what people are talking about when they refer to the Series A Gap. By the way, I don’t buy that argument, but more on that below.

The “Series A Crunch” line of reason goes like this:

Because Venture Capitalists raised their standards for investing, there are many companies who ‘deserve’ capital that can’t get it now. They’re square pegs that don’t fit into round holes. They’re tigers who can’t jump through the flaming hoops VC’s are beginning to set up.

If true, this would be a terrible and unfair tragedy for the current crop of startups.

Good thing it’s not.

I’m here to propose an alternate way to think about this issue. Our way of thinking about raising capital and our way of talking about it is flawed. The mental model for tech entrepreneurship goes like this: found a company, seed investment, series A, series B, series C, etc. But today that mental model is outdated.

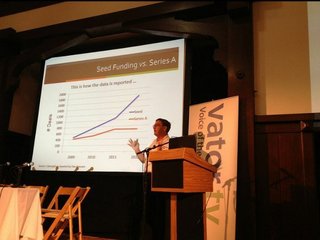

Here’s what’s really happened: The position Series A occupies has shifted to the right. It’s taken the place of what we used call Series B. This bumped Series B into the slot Series C used to occupy, and so on and so forth. There is nothing VC’s have created to fill the gap where Series A used to reside. And that’s fine.

What if I told you there was no big bad Series A crunch that precludes the success of all but the ‘hottest’ startups? What if I told you the current state of affairs is actually a good thing? And what if I told you that entrepreneurs can still get the money they need to build a business?

You’d ask… How?

Why there’s no ‘crunch’

The phrase ‘crunch’ implies that many qualified applicants are vying for the same spots in a VC’s portfolio. This is absolutely false. If you’re qualified for Series A, you’ll get it. The reason there’s a ‘crunch’ is that many of the companies who aren’t qualified think they are. If you’re not qualified yet, you need to keep working until you are. And there’s many ways to stay alive until then.

Let’s start with beginning startup capital. Gone are the days when seed-funding was strictly FFF. Now crowd-funding and seed-funds exist to bridge the gap. And of course organizations called accelerators, like my own StartEngine, are quite numerous.

At the next stage, you’ve got angel investors. An Angel round can add up to $2M; a seed-fund, between $300 and $500 thousand. If you’re really hot stuff, you could raise around $2.5M, but many make out comfortably at $1.5M.

These days, Angel investors signs convertible notes – nothing more than three or four page documents that don’t require due-diligence by a law-firm, nor does it need to be filed with the Secretary of the state of Delaware – hands the founders a check and is on board. One advantage to taking on an Angel is that Angels can get the ink on paper much quicker. Quick conclusions are suitable for the startup climate of today, because it mirrors reality. In general, things are now happening faster. And cutting a deal with Angels really is that much easier than dealing with the VC’s of yore.

And seed-funds? I’ve seen seed-funds throw their money directly in with angels for that convertible note (which they do because they tend to make decisions slower than the angels can), and I’ve seen them go to a price-round in exchange for equity. Heck, I’ve seen them do both

So what does this mean for our fledgeling founders? It means that early investing from seed-funds and Angels, if anything, can be easier to secure than it used to go with VC for those same stages. It means that we erroneously think of Series A as ‘the next step’ after seed, when that’s not the case anymore. Instead of going straight for Series A, you should find an alternative source of funding first, unless you’re one of the ‘chosen few’ who is immediately ready for VC.

The truth is, at the end of the day, the Series A has simply come to signify a different set of expectations. By design, the Series A round is supposed to be a weeding-out. And there is no real Series A crunch that ‘unfairly’ blows away otherwise suitable startups. More below.

Money should to chase talent, not the other way around.

When we consider entrepreneurs who can’t get access to VC, sometimes we default to thinking they’re ‘unlucky’ and ‘a victim of the current landscape.’

It is at this point that many quit. I’ve seen many companies shut down just because they couldn’t raise a series A. That’s not smart. They should have buckled down, lived frugally and found a different means. Whether founders of ‘crunched’ startups quitting is a good thing for a society or not is up for debate. I know one thing for sure: quitting is the only guaranteed way to torpedo your chances of success.

Instead of feeling sorry for yourself if you fail to raise money, look on the bright side. At least lack of funds bars your startup from going into growth-mode prematurely, which usually ends in a major flameout. Because your war chest is bare, you can only afford to stay scrappy, generally a good thing for your startup.

My advice? First, be one of those who doesn’t quit. Second, throw the traditional approach to fundraising out the window, because flipping the script is a powerful way become a hot commodity.

By the time you think you’re ready to raise the series A, the VC’s should be coming to find you. If you truly have the metrics to justify the series A investment, the VC’s will come to you.

One idea: declare one three hour window, once a week, and make it known this is the only time you’ll see investors. And enjoy the spectacle.

How to flip the fundraising script

These days, if you want to raise your series A you have to have your act together.

What does that mean? Unless you are a top-shelf charlatan, having your act together is a feat of business building. Having your act together is more about getting your hands dirty than ‘networking.’ If you have your act together, quickly you become magnetic to investors.

This doesn’t mean stay silent hope for a miracle to happen. Obviously you should stay visible on your blog and social media, and occasionally at events. It might not be a bad idea to follow my friend Mark Suster’s advice.

What I’m saying is don’t go around pounding on doors and begging for money. That does nothing but make you look desperate. It’s a good way to get the proverbial door slammed in your face. Sending a deck is a good way to look desperate (I advise our founders not to do this, but am not always successful in ensuring their restraint). If, however, your deck is a rocket ship then the VC’s will come to you.

That’s because VC’s read and watch for growth. VC’s are constantly talking to people and networking. Imagine them as a herd. A VC’s job is to find the gem. But you don’t find the Gem going through the pile of already-passed-over applications. Unless they see something really special, they won’t touch a company that asks them for money with a ten-foot pole. Many VC’s don’t invest unless someone they trust has already invested in that startup. No VC wants a deal that’s been stepped on, every VC wants a winner instead.

Alternative funding options

I’m going to assume you don’t have growth numbers like SnapChat. If you do have growth numbers like SnapChat, call me!

Let’s talk about what ‘the rest of us’ should do to ensure survival until the point where we can attract Series A love from VC’s. Or maybe you want to completely sidestep the hurdle of raising Venture Money – there’s something for everyone here.

Of course, there is a fifth option as well, and it is one that I can’t talk enough about: Remaining in Discovery Mode. Live frugally like you’re on a kibbutz. Live in a house with your founders, go to Costco, raise goats, whatever you feel like doing to save money and build a better product while you’re at it.

Why put yourself through a trial like that? If you’re committed to becoming successful, you need to prove you’re committed. That means you’ll explore every available option, even if it’s unconventional. If there’s a takeaway to this article, this is it.

The fundraising mindset I wish founders would adopt

If I could wish for one thing, it would be to see the following internal dialogue in up-and-coming founders of today andtomorrow:

Angel rounds instead of trying for VC? “Standard.”

Crowdfunding? “Let’s try it.”

Reverse merger? “Maybe it’s crazy enough to work.”

Complicated M&A bank schemes? “Could make sense, let me find the right mentor or advisor to help get it done.”

Staying frugal, cutting costs, building a truly robust business? “Count me in.”

Profitability as a fundraising scheme? “My life will never be the same.”

The question is now for you: what path will you choose if the way to Series A is blocked?

co-founder Activision, CEO Acclaim Games, Managing Partner of StartEngine.

All author postsOXcan combines proteomics and artificial intelligence for early detection

Read more...Nearly $265B in claims are denied every year because of the way they're coded

Read more...Most expect to see revenue rise, while also embracing technologies like generative AI

Read more...