By the early 1920’s General Motors realized that Ford, which was now selling theModel T for $290, had an unbeatable monopoly on low-cost automobile manufacturing.

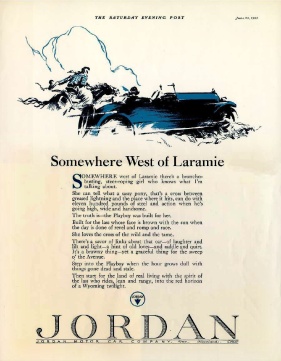

Other manufacturers had experimented with selling cars based on an image and brand. (The most notable was an ad by the Jordan Car company.) But General Motors was about to take consumer marketing of cars to an entirely new level.

Market Segmentation

General Motors had turned the independent car companies acquired by its founder Billy Durant into product divisions. But in a stroke of genius GM transformed these divisions into a weapon that Ford couldn’t match. With the rallying cry “a car for every purse and purpose,” GM positioned its car divisions (Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick and Cadillac) so they would cover five price segments – from low-price to luxury. It targeted each of its brands (and models inside those brands) to a distinct economic segment of the population.

Chevy was directly aimed at Ford – the volume car for the working masses. Pontiac came next, then Oldsmobile, then Buick.

The top-of- the-line Cadillac offered luxury and prestige announcing you had finally arrived at the top of the conspicuous consumption heap. Consumers could announce their status and lives had improved by upgrading their brands.

GM had one more trick to make this happen. Within each brand, the top of the line was just a bit less expensive than the lowest priced model of the next expensive brand. The goal was to convince the consumer to spend a little more to trade up to a more prestigious brand.

Market segmentation by price was somethingno other automotive manufacturer had ever done. While other car companies could compete with one of GM’s divisions, few had GM’s capital and resources to compete simultaneously with the onslaught of car models from all five divisions.

Planned Obsolescence While market segmentation allowed GM to use its divisions to reach a wider market than Ford or Chrysler, this didn’t solve the problem of market saturation. By the late 1920’s, most everyone in the U.S. had a car. And cars lasted 6 to 8 years. Even worse, the market was now filled with used cars that provided even lower cost basic transportation. Sloan, the General Motors CEO, faced two seemingly unsolvable challenges:

- How do you get consumers to abandon their perfectly fine cars and buy a new one?

- How do you turn a product that competed on price and features into a need?

In another stroke of genius, GM invented the annual model change. Sloan borrowed this idea from fashion where styles changed every year and applied it to automobiles starting in the 1920s. General Motors would change the external appearance of cars every year. Sloan preferred to call it “dynamic obsolescence.”

Styling and design became an integral part of GM’s strategy. Sloan hired Harley Earlto set up GM’s in-house styling staff. Earl would run it from 1927 to 1958.

Before Earl, cars were designed by in-house body-engineers who focused on practical issues like function, costs, features, etc. Each exterior component was designed separately to be functional – radiator, bumpers, hood, passenger compartment, etc. Some companies used 3rd party bodymakers to set the style , but GM was the first totake car design away from the engineers and give it to the stylists.

The concept of yearly “improvements”, whether styling or incremental technology improvements, every model year gave GM an unbeatable edge in the market. (Henry Ford hated the idea. He had built Ford on economies of scale – the Ford Model Tlasted for 19 years.) Smaller car makers could not afford the constant engineering and styling changes they had to make to keep competitive. GM would shut down all their manufacturing plants for a few months and literally rip out the tooling, jigs and dies in every plant and replace them with the equipment needed to make the next year’s model.

GM had figured out how to take a product which solved a problem – cheap transportation – and transform it into a need. It was marketing magic that wasn’t to be equaled until the next century.

By the mid-1950′s every other car company was struggling to keep up.

Mass Marketing Starting in the 1920’s and continuing for the next half century, automobile advertising hit its stride. Ads emphasized brand identification and appealed to consumers’ hunger for prestige and status. Advertising agencies created catchy slogans and jingles, and celebrities endorsed their favorite brands. General Motors turned market segmentation and the annual model year changeovers into national events. As the press speculated about new features, the company’s added to the mystique by guarding the new designs with military secrecy. Consumers counted the days until the new models were “unveiled” at their dealers.

Results

For fifty years, until the Japanese imports of the 1970’s, Americans talked about the brand and model year of your car – was it a ’58 Chevy, ’65 Mustang, or 58 Eldorado? Each had its particular cachet, status and admirers. People had heated arguments about who made the best brand.

The car had become part of your personal identity while it became a symbol of 20th Century America.

After Sloan took over General Motors its share of U.S cars sold skyrocketed from 12 per cent in 1920, until it passed Ford in 1930, and when Sloan retired as GM’s CEO in 1956 half the cars sold in the U.S. were made by GM. It would keep that 50% share for another 10 years. (Today GM’s share of cars total sold in the U.S. has declined to 19%.)

How the iPhone Got Tail Fins

Over the last five years Apple has adopted the GM playbook from the 1920′s – take a product, which originally solved a problem – cheap communication – and turn it into a need.

In doing so Apple did to Nokia and RIM what General Motors did to Ford. In both cases, innovation in marketing completely negated these firms’ strengths in reducing costs. The iPhone transformed the cell phone from a device for cheap communication into a touchstone about the user’s image. Just like cars in the 20th century, the iPhone connected with its customers emotionally and viscerally as it became a symbol of who you are.

—-

The desire to line up to buy the newest iPhone when your old one works just fine was just one more part of Steve Jobs’ genius – it’s how the iPhone got tail fins.

It’s one more reason why Steve Jobs will be remembered as the 21st century version of Alfred P. Sloan.