The FDA outlines draft guidance on AI for medical devices

The agency also published draft guidance on the use of AI in drug development

Read more...Growing up as a white girl in Pennsylvania, I was taught that being tan was beautiful. My wealthier classmates would go on vacations to Florida in the winter, coming back with the most glorious tans. And the moment that it started getting warm, everyone would spend excessive amounts of time outside in an effort to get as dark as possible. I hated this charade for completely banal reasons. There was no way to read a book when lying on my back (without limiting sun exposure) and I hated propping myself up on my elbows. I preferred to read indoors in chairs meant for reading. Needless to say, I didn’t get the point of tanning. Still, there were many summers when I tried. Status was just too important.

When I first went to Tokyo, I was shocked to find Shibuya covered in whitening ads. Talking to locals, I found that “white is beautiful” was a common refrain. As I traveled around Asia, I heard this echoed time and time again. I learned that those with Caucasian blood could get better acting and modeling jobs, that black Americans couldn’t teach English to Hong Kong kids (even though white Europeans who spoke English as a second language could). Whiteness (and blondness) was clearly an asset and I got used to people touching my hair with admiration. I was completely discomforted by this dynamic, uncertain of my own cultural position, and disgusted by the “white is beautiful” trope that was reproduced in so many ways. My American repulsion for the reproduction of racist, colonialist structures was outright horrified.

At some point, I went on a reading binge to understand more about whitening. It was just out of curiosity so I can’t remember what all I read but I remembered being startled by the class-based histories of artificial skin coloring, having expected it to be all about race. Apparently, tanning grew popular with white folks earlier in the 20th century to mark leisure and money. If you could be tan in winter, it showed that you had the resources to go to a warm climate. If you could be tan in summer, it showed that you weren’t stuck in the factories for work. (Needless to say, farmer tans are read in the same light.) Traipsing through the literature, I also learned that whitening had a similar history in Asia; being light meant that you didn’t have to work in the fields. Having always assumed that tanning was about looking healthy and whitening was about reproducing colonial structures, I found myself struggling to make sense of the class-based cultural dynamics implied. And uncertain of how to read them. Hell, I’m still not sure what to make of it all.

Of course, growing up in the States, I’ve seen a different version of light-skin fetishization. One that stems from our history of racism. One that is perpetuated in the black community with light skinned black folks being treated differently than dark skinned black folks by other black folks. So I don’t feel as though I have a good framework for making sense of how race is read in different countries. Or how it’s tied into the narratives of classism and colonialism. Or what it means for modifying skin tone. All that I know is that the marketing of skin coloring products is far more complex than I originally thought. That we can’t see it simply in light of race, but as a complex interplay between race, class, and geography. And that how we read these narratives is going to depend on our own cultural position.

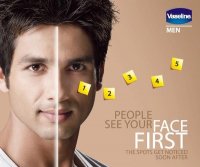

So, moving forward to 2010, Vaseline puts out a Facebook App for virtual skin whitening targeted at Indian men. This virtual product is an ad for its whitening product, but it also serves to allow users to modify their skin tone in their pictures. Needless to say, the signaling issues here are intriguing. I can’t help but think back to Judith Donath’s classic Identity and Deception in the Virtual Community. But there are also huge issues here about race and class and national identity. As people start finding out about this App, a huge uproar exploded. Only, to the best that I can tell, the uproar is entirely American. With Americans telling other Americans that Vaseline is being racist. But how are Indians reading the ads? And why aren’t Americans critical of the tanning products that Vaseline and related companies make? Frankly, I’m struggling to make sense of the complex narratives that are playing out right now.

So, moving forward to 2010, Vaseline puts out a Facebook App for virtual skin whitening targeted at Indian men. This virtual product is an ad for its whitening product, but it also serves to allow users to modify their skin tone in their pictures. Needless to say, the signaling issues here are intriguing. I can’t help but think back to Judith Donath’s classic Identity and Deception in the Virtual Community. But there are also huge issues here about race and class and national identity. As people start finding out about this App, a huge uproar exploded. Only, to the best that I can tell, the uproar is entirely American. With Americans telling other Americans that Vaseline is being racist. But how are Indians reading the ads? And why aren’t Americans critical of the tanning products that Vaseline and related companies make? Frankly, I’m struggling to make sense of the complex narratives that are playing out right now.

What intrigues me the most about the anti-Vaseline discourse is that it seems to be Americans telling the global south (which is mostly in the northern hemisphere) that they’re being oppressed by American companies. The narrative is that Vaseline is selling whitening products to perpetuate colonial ideals of beauty. In the story that I’m reading, those seeking to consume whitening products are simply oppressed voiceless people who clearly can’t have any good reason for wanting to purchase these products other than their own self-hatred wrt race. (Again, no discussion of fake tanning products.) And in making Vaseline out as an evil company, there’s no room for an interpretation of Vaseline as a company selling a product to a market that has demanded it; they’re purely there to impose a different value set on a marginalized population. Don’t get me wrong – I think that our skin color narratives are wholly fucked up and deeply rooted in racism. But I’m not comfortable with how this discussion is playing out either. And I can’t help but wonder for how many people the Vaseline App controversy is the first time they’ve seen skin whitening products.

This uproar is interesting to me because it highlights cultural collisions. These products are everywhere in Asia but they’re harder to find in the States. Yet, with social media, we get to see these cultural differences collide in novel ways. When we go to foreign countries and talk to people from different cultural backgrounds, we learn to read different value sets even if they bother us. We have room to do that in those contexts. But when we encounter the value sets online sitting behind our computers in our own turf without a cultural context, all sorts of misreadings can take place. I’m seeing this happen on Twitter all the time. Cultural narratives coming from South Africa that mean one thing when situated there but are completely misinterpreted when read from an American lens. I love Ethan Zuckerman’s amazing work on xenophilia. But I can’t help but be curious about all of the xeno-confusion that’s playing out because of the cultural collisions. And I worry that us Americans are just reading every global narrative on American terms. Like we always do. And while this might be great for challenging colonialism, I worry that it is mostly condescending and paternalistic.

And that leaves us with a difficult challenge: how do we combat racism and classism on a global scale when these issues are locally constructed? How do we move between different cultural frameworks and pay homage to the people while seeking to end colonialist oppression? I don’t have the answers. All I have is confusion and uncertainty. And confidence that projecting American civil rights narratives onto other populations is not going to be the solution.

The agency also published draft guidance on the use of AI in drug development

Read more...The biggest focus areas for AI investing are healthcare and biotech

Read more...It will complete and submit forms, and integrate with state benefit systems

Read more...