has blogged about consistently, investors need to know what the

underlying securities are worth inside banks, brokerage firms,

insurance companies, hedge funds, private equity funds, and yes venture

capital funds.

The FASB (which governs accounting standards in this country) recently issued a new rule called FAS157.

I’m not going to get technical on you and the accountants in the

community can weigh in via the comments if they feel the need for more

rigor in this discussion.

In layman’s terms, FAS157 says that you have to value your investments at ‘fair market value’.

I’ve been dealing with valuing venture investments every quarter

since I got into the VC business in the mid 80s. One of the big roles I

had at my first VC job was the help manage the annual audit process and

I’d prepare the schedules of investment for our firm’s funds every

quarter

Back then, we did it the old school way. We’d carry our investments

at the ‘lower of cost or market’ and rarely write them up without a new

financing event. Even with a new financing event, we’d often continue

to carry the investments at cost if we felt that the markup to the next

round price was ‘shaky’. That could be because it was an internal

round, a round led by strategic investors, or just a wildly inflated

valuation that we were uncomfortable with.

On the other hand, we were quick to mark things down when the

investments soured. We’d often mark an investment down to one dollar to

signify that it was still unrealized but we felt it had no upside

potential.

The net result of this approach is that the fund would always be

undervalued until the investments were realized and the distributions

had been made in full. And everyone was mostly fine with that approach

because almost all LPs at that time held their fund investments to

maturity and didn’t care about interim valuations. They cared about

cash out/cash in and not much else.

All that has changed and the venture business is a different place

now. Interim valuations (and the associated returns) matter quite a bit

when you go out to raise another fund. Also, the LPs are now selling

their positions in the secondary market and this year we’ll likely see

more of that than ever before. So the carrying value of the investments

is starting to matter.

And then comes these new rules from FASB. Our auditors, and I

suspect every VC firm’s auditors, want us to be rigorous about our

valuation methodology and try, each quarter, but particulalry at year

end, to come up with a calculation of ‘fair value’ for every company

we’ve invested in and every underlying security we own in those

companies.

Over the past week, as the audit season hits, I’ve had a number of

conversations with other VCs about how we are valuing companies we

share an interest in. And from those conversations, its clear to me

that there are a lot of different approaches being taken out there.

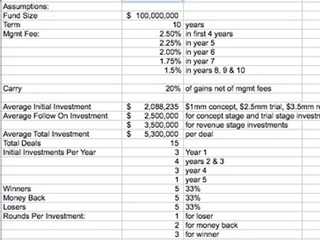

So I thought it would be a good idea to blog about how we do it. First, we start with two crack members of our team, Andrew and Eric, who do most of this work. I hope they’ll weigh in with comments and correct me where I’ve mis-stated something.

They have created a spreadsheet template that we use for each

company. We then go out and find comparable private and, ideally,

public companies for each of our investments. We like to have at least

three ‘comps’ and often use four or five.

Then we calculate multiples of revenues, ebitda, and sometimes other

measures of ‘traction’ like size of audience (UVs per month) for all

the comps. We then take an average and get a baseline comp for each

portfolio company. We back out excess cash less debt from the market

prices when we calculate these comps.

When we use private companies and M&A transaction values that

happened some time ago (we don’t use comps that are more than 18-24

months old) we’ll apply a market factor to them. For example, we’d take

the Bebo sale price of $850mm and cut it roughly in half because the

market has dropped in half since Bebo was sold. We do the same with

comps for venture deals like the latest private round for WordPress.

We then collect the financial and other important data points for

our companies for the current and next fiscal year and apply the

relevant comp to that company and calculate an enterprise value. If the

portfolio company has a significant amount of excess cash on its

balance sheet we will add that minus any debt to the enterprise value

to get a market value.

Then we assume we sold each and every company in an M&A

transaction at that market price and do a liquidation analysis and

determine the value in that scenario of each underlying security. And

that’s what we carry them at each quarter.

This is a tortuous process and produces some very non-intuitive

results. For example, we are going to mark down the unrealized gain of

the two companies in our portfolio that had the best fourth quarters of

all of our companies. Seems strange that we be marking down the

carrying values of our two best companies doesn’t it? But the reason is

that even though they both significantly beat their plan in Q4, the

comps we use for both came way down in the fourth quarter.

So we take the adjustments and explain it to our investors in the reports and on the investors calls we do every quarter.

We also have the opposite problem that sometimes we are forced to

write our investments up to levels we are not comfortable with. When

their comps have big and probably temporary increases in stock price,

our companies get written up. Which inevitably leads to a markdown in a

future quarter.

The public market investors who are reading this are probably

laughing right about now and thinking that it’s about time the private

equity and VC firms had to deal with vagaries of the market.

But I’m not sure this is all good news for the investors in VC

funds. We are going to see a lot more volatility in fund valuations and

the ways of the past where you had slow but steady increases in fund

value are gone. VC interim returns are going to get more correlated

with the market and we’ll all end up spending countless hours

explaining away certain numbers that are on the books but make no sense.

And, like has happened to me over the past couple weeks, VCs are

going to have to talk more to our colleagues about how we are valuing

our common investments so we can take the phone calls from our common

LPs and explain why we’ve marked something up but our colleagues have

marked it down.

There’s a silver lining in all of this, including the IRS 409a

pronouncement of a few years ago that has created a whole industry of

private company valuation firms and, if anything, even lower stock

option grant prices, and that is that we are starting to collect a huge

data set of private company valuations over time.

This, combined with the efforts of a few brave souls to create

secondary markets for private company stock is going to lead to more

data, more transparency, and more liquidity without having to register

and do an IPO or sell your company.

But right now, it all feels like major pain in the butt.

(For more from Fred, visit his blog)

(Image source: RDR.zazzle.com)