Published July 24, 2020, in the Harvard Business Review. Reposted with permission.

Confusion reigns concerning the future course and consequences of the novel coronavirus pandemic in the United States. But one thing is certain: The health care system that emerges from the pandemic will not be the same. The question is, how will it be transformed? We attempt to answer that by posing alternative scenarios based on assumptions about key parameters that can heavily influence how the pandemic evolves. The analysis makes clear that in its pending stimulus package, Congress needs to take steps to prevent potentially long-lasting damage that COVID-19 may inflict on the health care system.

Three factors will prove most critical to the pandemic’s future: the public’s use of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as facial coverings and physical distancing; the availability, efficacy, and public acceptance of one or more vaccines; and the availability and efficacy of anti-viral therapies. There are obviously dozens of other possible influences on the course of the pandemic such as whether “herd immunity” might someday slow the spread. But these three factors have the greatest potential to decisively alter the course of COVID-19 in the United States and elsewhere if we succeed in instituting one or more of them.

To explore how the pandemic may evolve, we posit three scenarios with respect to these three factors:

- A dream case in which everything goes as well as could reasonably be expected.

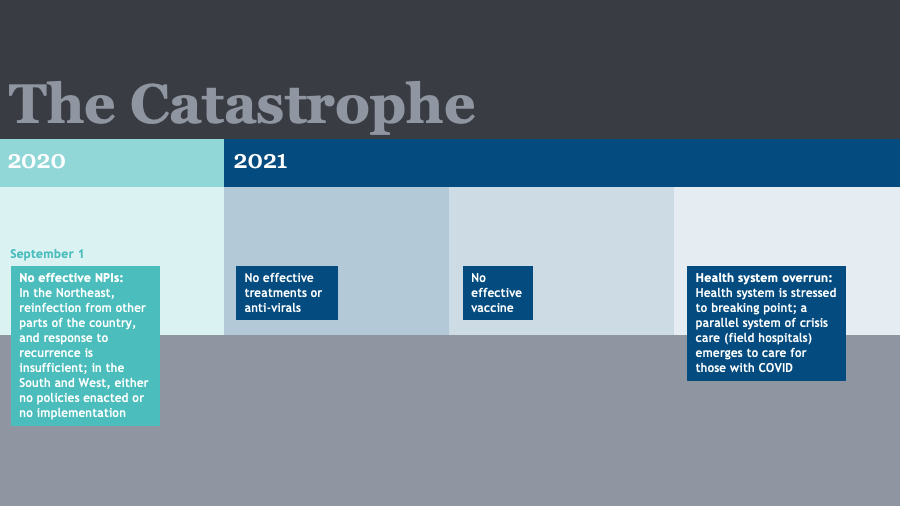

- A catastrophic case in which everything goes badly.

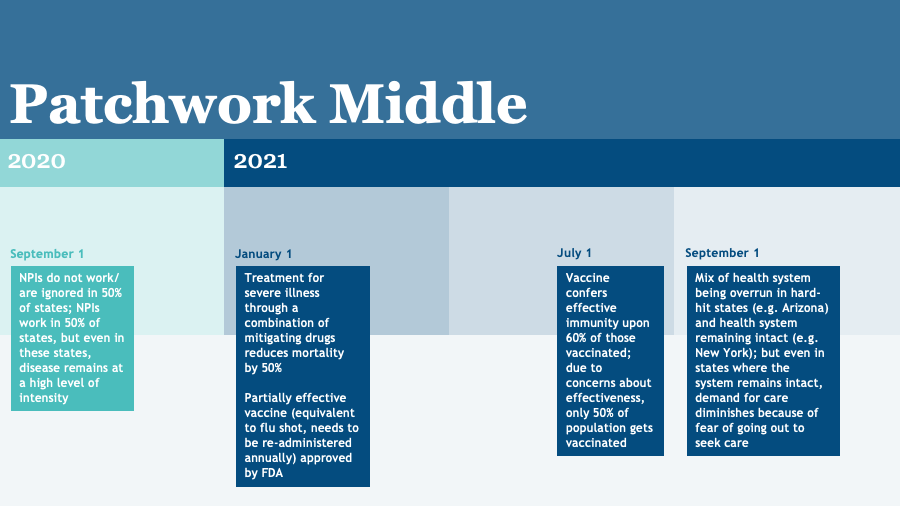

- A middle case in which some things go well, but others don’t.

In evaluating the consequences of these scenarios for the nation’s health care system, we make one important additional assumption: The linchpin for a return to the health care system’s pre-pandemic “normal” state lies with the nation’s ability to assure the safety of segments of the population that are most vulnerable to the pandemic, especially the elderly and the chronically ill. These groups comprise the 5% of the population that consumes 50% of health care resources. Only when they feel safe to venture out will health care institutions experience a vigorous recovery in demand for their services. While telehealth can partially compensate for the falloff in the use of services, it will go only so far. It cannot replace hips or knees, do colonoscopies, or insert cardiac stents.

Scenario 1: The Dream Case

It plays out as follows:

- By September 1, governors and other political leaders have widely and aggressively implemented NPIs throughout the United States with strong public compliance.

- By November 1, highly effective anti-virals have reduced the mortality from COVID-19 among the elderly to the level of influenza: less than 1% of those infected.

- By January 1, at least one vaccine equivalent in efficacy to smallpox or measles is available for widespread use.

- By July 1, 60% of the American public is vaccinated, including most high-risk individuals, creating effective herd immunity.

- By December 1, 2021, the pandemic is declared over in the United States.

This highly optimistic scenario suggests that by early fall, viral transmission will be falling rapidly throughout the United States and that by late fall or early winter, it will be low enough for high-risk groups to feel safe. At that point, demand for health care services should begin to grow rapidly, accelerating with the arrival of effective therapies and a vaccine. Within 12 months, the health care system should be experiencing inpatient and outpatient volumes that equal or exceed pre-pandemic levels.

However, the health care system that returns to “normal” in 12 months will likely be different from the system of February 2020. A significant number of financially-weak hospitals and clinical practices will have closed their doors or merged with strong local institutions that have the capital to ride out the pandemic storm. There will be fewer primary care practices, community health centers, rural hospitals, independent small and moderate size hospitals, inner-city safety-net hospitals, and money-losing services of all types. Large systems will have grown larger and more dominant in local markets. The weak will be weaker and the strong stronger.

The market power of dominant local health care organizations may grant them even more leverage to negotiate higher prices from local payers in the future. Patients will have reduced choice of providers. The national capacity to offer effective primary care — the key to prevention and control of chronic illness — will be diminished, at least in the short term.