The new model for schools and education

A five-point plan that we should invest in

\

\

There’s a scene in the new Star Trek where kid Spock is in an individual learning pod with poetry, calculus and whales floating by. This scene is immediately followed by him swapping blows with a crew of sociopathic Vulcan classmates. I think these two scenes sum up my concerns about an overly automated education. Sure, these Vulcan kids would nail their standardized test, but they’re also sorely lacking in social skills and grace.

Computers can’t do everything, but they can do some things. But I’m jumping ahead. First, let’s frame the problem.

On a comparable basis of education spending / GDP, the US is at the top end of developed countries.

Here’s a clip from the World Bank list:

- Norway – 6.8% (education spend / GDP)

- Saudi Arabia – 6.4%

- France – 5.6%

- United Kingdom – 5.5%

- United States – 5.5%

- Brazil – 5.1%

- Canada – 4.9%

- Australia – 4.5%

- Germany – 4.5%

- Japan – 3.5%

It’s important to note that the US is much bigger than most of these countries (we spend over $800 billion a year on education. Germany, for example spends closer to $130 billion). We also have a much more diverse economy than most countries. If you take the European Union as a whole (I think our closest comparable), in aggregate we’re spending about the same, if anything a bit more as a percentage of GDP (there wasn’t data for China and India).

One really important factor in US education spending is the disparity between rich and poor states, and even more acutely, the difference between rich and poor districts within those states. Jonathan Kozol speaks very well to these issues. Educational resources are clearly not evenly distributed. But I don’t want to digress into definitions of “fair,” that’s a different question from the one I want to discuss now.

What I want to highlight is that we’re spending a lot, and frankly, we’re not likely going to be able to spend much more. A few billion here-and-there doesn’t move the macro $800 billion needle. We’re not going to get to 10% of GDP for education.

We have to make 5-6% of GDP work.

The good news is I don’t think the world’s best schools are out of reach. I contend we can do it on less than we’re currently spending, and I believe the marginal improvements would be greatest for the least well off school districts.

Here are my five priorities for kids in school:

1. to be literate in a core set of topics (math, language, history, geography, science);

2. to get plenty of physical exercise;

3. for them to have opportunities to be creative (art, dance, music);

4. to learn social skills (sharing, community) and for them to have instilled in them basic pan-American values (freedom, liberty, justice, equal opportunity) ;

5. have a basic preparedness for work and life.

When I drop my kids off in the morning this is the blend of activities in which I’d love for them to be immersed. I’m not a tiger-mom, nor a French-parent. Just a regular guy who wants a happy, healthy, engaging environment for his kids – and who believes the rest will generally take care of itself.

To this end, here is how I believe we can radically change the US (and one day, perhaps global) education system, increase student engagement, and get much more for our money.

First, we can collapse the cost of delivering education for core literacy topics. I’m fine if my kids learn subjects like math and English substantially from a computer. I believe, as demonstrated by Professor Sugata Mitra, that kids, in the right environment, can teach each other, and learn in groups. I’m completely confident we can create outstanding online curricula and could put hundreds of kids together, or in groups, or on their own (with the ability to get help from teachers, assistants and their peers) to learn these subjects for a few hours per day.

Watch what Salman Khan has done with Khan Academy – the lecture is now the homework and the homework is now done in class. He calls it the death of the “one size fits all lecture.” His thesis (and I agree) is that the talking part of class is best done at home, at the student’s pace, and the class is the venue for collaboration and assistance around the application of the subject (the thing previously known as homework!). This is a powerful and revolutionary innovation.

This model will be enabled by tailored instruction and seamlessly blends home and schoolwork.

I say every kid in America gets a laptop (55 million kids in school – that’s $5.5 billion at $100 per laptop if we had to buy a new one, for every kid, each year – which we wouldn’t). Yes, that’s expensive, but less than 1% of what we spend on education each year! We could radically change the curriculum, tools, texts, feedback loops (see Khan video above on feedback loops)…everything.

Second, Kids should be moving, a lot. One third of kids in the U.S. are overweight, while well under 10% of schools require daily physical education. I’d wager the #1 competitor for spending money on education is going to be healthcare – let’s get kids in shape and re-purpose the money for the long run! We can augment the P.E. teaching staff with parents and part-timers. Core P.E. staff flanked by whip crackers.

Third, I’d move the money we save on classroom literacy training to the arts (broadly), our kids need to be creative. For an outstanding discussion of literacy vs. creativity listen to Sir Ken Robinson’s TED talk (this has to be in the hall of fame for TED talks). Creativity as defined by Sir Ken is “the process of having original ideas which have value,” to this end, hear his discussion of the education of Gillian Lynne the British choreographer and director (minute 15 in the talk). Condoleezza Rice calls it “appalling” that the arts are “extracurricular.” The 9/11 commission said the U.S.’s most important failure in anticipating the terrorist attacks was “one of imagination.”

Fourth, I’d like to reinvigorate a deep appreciation of the American system of government, the fragility of freedom, and the power of an open society. I think our country has lost the fear of totalitarianism, and I believe that fear should be a drum beat in our lives.

For some reason, a while back, I was reading the Wikipedia profile of Sacha Baron Cohen (Borat, but even better as King Julian in Madagascar), in the middle he’s quoted as saying the following:

“When I was in university, there was this major historian of the Third Reich, Ian Kershaw, who said, ‘The path to Auschwitz was paved with indifference.’ I know it’s not very funny being a comedian talking about the Holocaust, but it’s an interesting idea that not everyone in Germany had to be a raving anti-Semite. They just had to be apathetic.”

That thought has stuck with me for some time. Apathy is a social cancer, and I think our kids need a deep appreciation of the work it takes to maintain a free and open society. Karl Popper primers for all first graders!

Fifth, and last, on my list is greater real world application of education. Kids are excited by opportunities to make money. They like to learn practical skills. They love to be engaged in “the real world.”

I spent much of my childhood in the British system of education (in London and Fiji). The British do a great job of teaching life skills. I used to really enjoy my home economics classes in London where we learned how to bake pies and muffins. In Fiji, at what must have been around 8th grade, we had a full accounting class! I can remember Mr. Aziz at-the-ready to reprimand a student for getting his or her debits and credits mixed up. It was fun, I felt like I knew how to do “real stuff.” I think giving kids opportunities to apply what they know, in increasingly real world contexts is good for them.

What’s simultaneously depressing and invigorating about this list is that our system is funneling massive resources into item 1 – classroom-based literacy education – while draining the life out of items 2 through 5.

We’re so far off the mark it’s almost comical. This also means there’s so much low hanging fruit that we’re going to be able to make astounding advances in a short time. With new technology, new school designs, and a new conceptualization of the staff makeup at schools, I believe we can radically change what our kids do all day, how they think, the shape they’re in, how they treat one other, and how well prepared they are for life.

Sir Ken quotes Arthur C. Clarke in his talk: “If children have interest, then education happens.” I believe that, and I believe we can expect more from our kids, and that our kids can be empowered to help one other.

As important, we can afford what I’m proposing above. In fact, if you look carefully, you can see flakes of this new model falling all around you.

Bring on the snowball.

(Note: This post is part of a conversation that started over at the weover.me blog. What is weover.me? We’re hoping weover.me can be a venue for discussion. As Simon Sinek said in his talk at Ted: It’s not “what you do” but “why you do it.” Weover.me exists to create conversation around ideas, values, topics, opinions, and beliefs that matter. We live, we work, and we play everyday, but on any day do we pause to think about why we do what we do? Few venues exist where honest, raw, and authentic conversation can happen around this question. weover.me exists to change this! The mission of weover.me also recognizes as its starting point that we’re better off if we try to put the needs of the “we” before the needs of “me”

Innovation in education will be the next topic to discuss live in Berkeley on Thursday, May 24. Click here for more information.)

(image source: skywaterblue)

(Note: See below for stories about private-sector innovation across education)

Related News

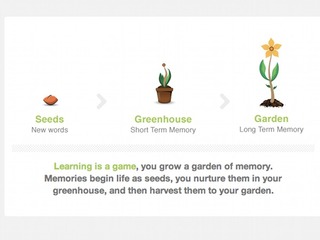

Memrise raises $1.05M to gamify language learning

2tor raises $26M to revamp online college education

Online educator StraighterLine raises $10 million

Online education company Coursera raises $16 million

Edmodo nabs $15M for bulking up 'Facebook' of education

Piazza gets $1.5M infusion for student Q&A forum