The principles of product-development flow

Complete more cycles of learning to generate more information in each cycle

If you've ever wondered why agile or lean development techniques work, The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development by Donald G. Reinertsen is the book for you. It's quite simply the most advanced product development book you can buy.

If you've ever wondered why agile or lean development techniques work, The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development by Donald G. Reinertsen is the book for you. It's quite simply the most advanced product development book you can buy.

For those who hunger for a rigorous approach to managing product development, Donald Reinertsen's book is epic. Myths are busted on practically every page, even myths that are associated with lean/agile. For example, take the lean dictum of working in small batches. I push this technique quite often, because traditional product development tends to work in batches that are much too large. Yet it's not correct to say that batch sizes should be as small as possible. Reinertsen explains how to calculate the optimal batch size from an economic point of view, math and all. It's wonderful to have an author take these sorts of questions seriously, instead of issuing yet another polemic.

The book is structured as a series of principles, logically laid out and briefly discussed - 175 in all. It moves at a rapid clip, each argument backed up with the relevant math and equations: marginal profit, Little's law, Markov processes, probability theory, you name it. This is not for the faint of heart.

The use of economic theory to justify decisions is a recurring theme of the book. Its goal is to help us recognize that every artifact of our product development process is really just a proxy variable. Everything: schedules, efficiency, throughput, even quality. In order to trade them off against each other, we have to convert their impact into economic terms. They are all proxies for our real goal, maximizing an economic variable like profit or revenue. Therefore, in order to maximize the true productivity (aka profitability) of our development efforts, we need to understand the relationships between these proxy variables.

Just for the economic explanations, this book would

be worth the price of admission. But it goes beyond that, including

techniques for improving the economics of product development.

Reinertsen weaves together ideas from lean manufacturing, maneuver

warfare, queuing theory, and even the architecture of computer

operating systems and the Internet. It's refreshing to see ideas from

these different domains brought together in a coherent way:

If we limit ourselves to the relatively simple WIP [work-in-progress] constraints used in lean manufacturing, we will underexploit the power of WIP constraints. Instead, we will explore some of the more advanced ideas used in the world of telecommunications.Reinertsen is keenly aware of what makes product development different from other business functions, like manufacturing, that we sometimes use as a metaphor. Product development deals in designs, which are fundamentally intangible. This is why product development routinely creates disruptive innovation, because our ability to invent new products is limited only (well, primarily) by our capacity for imagination. And yet it is this same ephemeral nature that gives rise to the most difficult problems of product development: how to tell if we're making progress, the high variability of most product development tasks (e.g. will this bug take 5 minutes or 5 weeks to fix?), and the resulting extreme uncertainty that is, incidentally, the environment where startups thrive.

If we showed the Toyota Production System to an Internet protocol engineer, it is likely that he would remark, "That is a tail-dropping FIFO queue. That is what we started with on the Internet 30 years ago. We are now four generations beyond that method." I mention this to encourage you to look beyond the manufacturing domain for approaches to control flow.

To motivate you to buy this book, I want to walk you through some of Reinertsen's indictment of the status quo in product development, which is based on his extensive interviews, surveys, and consulting work. He starts the book with twelve cardinal sins. See if any of these sound familiar:

- Failure to correctly quantify economics.

- Blindness to queues.

- Worship of efficiency.

- Hostility to variability.

- Worship of conformance.

- Institutionalization of large batch sizes.

- Underutilization of cadence.

- Managing timelines instead of queues.

- Absence of WIP constraints.

- Inflexibility.

- Noneconomic flow control.

- Centralized control.

To understand the economic cost of queues, product developers must be able to answer two questions. First, how big are our queues? Today, only 2 percent of product developers measure queues. Second, what is the cost of these queues? To answer this second question, we must determine how queue size translates into delay cost, which requires knowing the cost of delay. Today, only 15 percent of product developers know the cost of delay. Since few companies can answer both questions, it should be no surprise that queues are managed poorly today.Or take this indictment of our worship of efficiency:

But, what do you product developers pay attention to? Today's developers incorrectly try to maximize efficiency ... Any subprocess within product development can be viewed in economic terms. The total cost of the subprocess is composed of its cost of capacity and the delay cost associated with its cycle time. If we are blind to queues, we won't know the delay cost, and we will only be aware of the cost of capacity. Then, if we seek to minimize total cost, we will only focus on the portion we can see, the efficient use of capacity.Or consider principle B9: The Batch Size Death Spiral Principle: Large batches lead to even larger batches:

This explains why today's product developers assume that efficiency is desirable, and that inefficiency is an undesirable form of waste. This leads them to load their processes to dangerously high levels of utilization. How high? Executives coming to my product development classes report operating at 98.5 percent utilization in the precourse surveys. What will this do? [This book] will explain why large queues form when processes with variability are operated at high levels of capacity utilization.

The damage done by large batches can become regenerative when a large batch project starts to acquire a life of its own. It becomes a death march where all participants know they are doomed, but no one has the power to stop. After all, when upper management has been told a project will succeed for 4 years, it is very hard for anyone in middle management to stand up and reverse this forecast...This snippet is characteristic of Reinertsen's writing style and reasoning. He shows how the actions of people inside traditional systems are motivated by their rational assessment of their own economics. By setting up the wrong incentives, we are rewarding the very behaviors that we seek to prevent. Reinertsen has a visceral anger about all that waste, and his stories are crackling with disdain for the people who manage such systems - especially when their actions are motivated by intuition, voodoo, or blindness. Startups are frequently guilty as charged - the 4-year death march example above could be written about dozens of venture-backed companies slogging it out in the land of the living dead.

Our problems grow even bigger when a large project attains the status of the project that cannot afford to fail. Under such conditions, management will almost automatically support anything that appears to help the "golden" project. After all, they want to do everything in their power to eliminate all excuses for failure.

Have you had trouble buying a new piece of test equipment? Just show it will benefit the "golden" project and you will get approval. Have a feature that nobody would let you implement? Find a way to get it into the requirements of the "golden" projec. These large projects act as magnets attracting additional cost, scope, and risk...

At the same time, large batches encourage even larger batches. For example, large test packages bundle many tests together and grow in importance with increasing size. As importance grows, such test packages get even higher priority. If engineers want their personal tests to get high priority, their best strategy is to add them to this large, high-priority test package. Of course, this then makes the package even larger and of higher priority.

Reinertsen does not speak about startups specifically - his book is meant to speak broadly to product development teams across industries and sectors. Yet his analysis of the sources of waste in development and the remedies that allow us to iterate faster are especially useful for startups. There is an important caveat, however. Product development in established companies and markets has a clear economic rationale to judge effectiveness and productivity. The goal is to increase profitability by making high-ROI investments in new products. To give one example, Reinertsen emphasizes the power of measuring the cost of delay (COD) of a new product. That is, in order to make economically rational decisions about cycle time for a given process, we should understand what it costs the company if the products produced by that process are delayed by, say, one day. Armed with that information, we can make rational trade-offs. Take one of Reinertsen's example:

Unhappy with late deliveries, a project manager decides he can reduce variability by inserting a safety margin or buffer in his schedule. He reduces uncertainty in the schedule by committing to an 80 percent confidence schedule. But, what is the cost of this buffer? The project manager is actually trading cycle time for variability. We can only know if this is a good trade-off if we quantify both the value of the cycle time and the economic benefit of reduced variability.

Does

this sound familiar? Many of the startups I talk to - and their boards

- seem to equate ability to "hit the schedule" with competence and

productivity. Yet timely delivery of new features often comes at the

expense of agility, especially if cycle times are long. That is often a

bad trade (although, as I'm sure Reinertsen would hasten to add, not

always!). For example, many startups would do better by removing

buffers from their schedules, embracing the variability of their

delivery times, and reducing their cycle times.

Even worse, and

unlike their established counterparts, startups often experience a

non-quantifiable cost of delay. In a truly new market, we face no

meaningful competition, there are no tradeshows to present at, and

customers are not clamoring for our product. This means that there are

no external factors that argue for shipping product on any given day. A

day delay has almost no cost, as far as profitability is concerned.

Remember that startups operate by a different unit of progress: what I

call validated learning about customers.

Any activity that promotes learning is progress, and productivity needs

to be measured with respect to that. And that's also where we need to

modify some of the specific practices Reinertsen recommends. If the

product development team can be engaged in activities that promote

business learning at the expense of shipping - or even selling -

product, that's a good trade. Hence the need for partitioning our

resources into a separate problem team and solution team. As with any methodology, applying the principles faithfully may require modifying the practices to fit a specific context.

Let

me close with an excerpt of Reinertsen at his best, using an unexpected

example to illustrate the power of fast feedback to make learning more

efficient:

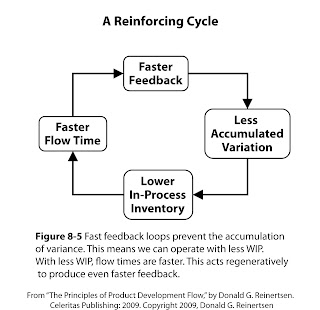

It should be obvious that fast feedback improves the speed of learning. What may be less obvious is that fast feedback also increases the efficiency with which we generate information and learn new things. It does this by compressing the time between cause and effect. When this time is short, there are fewer extraneous signals that can introduce noise into our experiment.There's far more material in this book that I would love to be able to excerpt. Unfortunately, each principle builds on the previous ones so tightly that it's hard to form coherent excerpts without quoting the whole thing. And that's exactly my point. When we're ready, this book has a tremendous amount to teach all of us. It's not a beginner's guide, and it doesn't hold your hand. Instead, it tackles the hard questions head-on. I've read it and re-read it; for a process junkie like me, I just can't put it down. I hope you'll enjoy it as much as I have.

Team New Zealand designed the yacht that won the America's Cup. When they tested improvements in keel designs, they used two virtually identical boats. The unimproved boat would sail against the improved boat to determine the effect of a design change. By sailing one boat against the other, they were able to discriminate small changes in performance very quickly.

In contrast, the competing American design team used a single boat supplemented by computer models and NASA wind tunnels. The Americans could never do comparison runs under truly identical conditions because the runs were separated in time ...

Team New Zealand completed many more cycles of learning, and they generated more information in each cycle. This ultimately enabled them to triumph over a much better funded American team. It is worth noting that Team New Zealand explicitly invested in a second boat to create this superior test environment. It is common that we must invest in creating a superior development environment in order to extract the smaller signals that come with fast feedback.

The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development

Related News

Reid Hoffman: Pursue as a learning cycle

Transition to a Web-based business

The 17 musts to get a product off the ground

Eric Ries on pivots and continuous deployment